Sometime in the coming weeks, a convoy of trucks will depart Vidalia, Louisiana, for Trion, Georgia, carrying 45 antique Draper X3 shuttle looms, 45 Picanol President shuttle looms, and the fate of American-made selvedge denim. The story of how those looms got to Vidalia, why they’re headed to Georgia, and how they became a stand-in for all that was great about the bygone days of American-made clothing begins in 2017. That’s when the fabled Cone Mills White Oak denim plant in Greensboro, North Carolina, announced it was shutting its doors after 112 years in business. As the main supplier of denim to Levi’s and many other famed brands for much of the 20th century, it’s hard to overstate how important White Oak was to the history of blue jeans. As the country's last industrial-scale producer of selvedge denim—the old-school fabric prized for its authenticity and the unique patina it develops over time—the closure of White Oak wasn’t just the end of a company; it was the end of an era.

“It closed a chapter on American denim that we're never going to have again,” says Roy Slaper, the founder of Roy Denim and a longtime White Oak devotee. What made White Oak’s denim so special wasn’t just the building or the generations of skilled workers who spent their careers there, Slaper explains; it was the looms themselves. “The Draper X3, that’s the loom,” he says.

Narrower and slower than their modern counterparts, White Oak’s Draper X3s date back as far as the 1940s, and the fabric they produced had an unmistakable look and feel. “The looms were in a building that was very old, and the wooden floor would bounce up and down as they worked,” Slaper says. “This introduced inconsistencies in the weaves that would not have been there otherwise.” Slaper’s stockpile of White Oak denim allowed him to continue making his namesake jeans until 2021. After that, he says, “I was done.”

Fortunately, the denim world didn’t have to wait long for a savior. In 2018, an ambitious startup called Vidalia Mills acquired White Oak’s shuttle looms and relocated them to its newly inaugurated plant in Vidalia, Louisiana. Vidalia Mills promised to continue White Oak’s legacy and bring large-scale denim production back to the United States, but the company ultimately fell far short of its ambitions and collapsed under more than $30 million in debt in late 2024. Once again, the fate of American selvedge hung in the balance while rumors swirled about who might pick up where Vidalia left off.

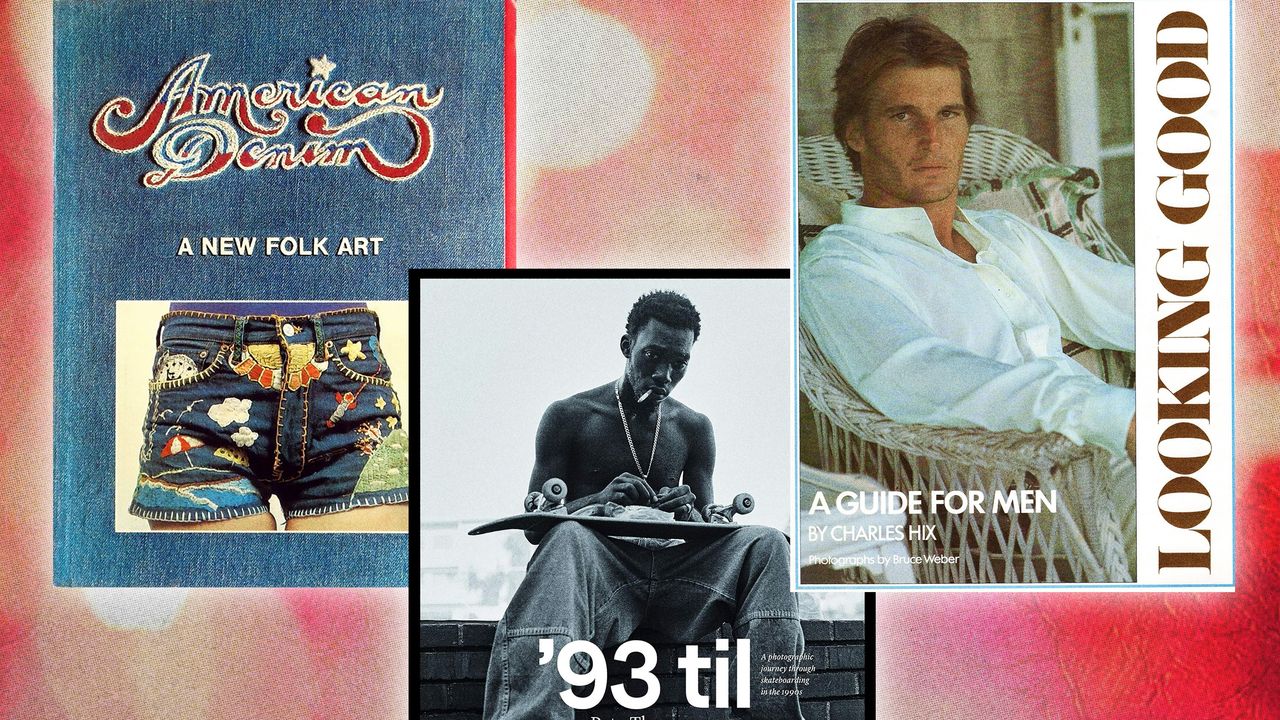

Cone Mills’s Draper X3 looms, seen here at the iconic White Oak plant in 2012, will soon be delivered to Mount Vernon Mills in Trion, Georgia.

Bloomberg/Getty Images

Some insiders speculated that a Japanese company would buy the looms. Others believed that a coalition of American denim brands should step up. Some, like Evan Morrison, a selvedge denim specialist at the White Oak Legacy Foundation (W.O.L.F.), saw Mount Vernon Mills, an 180-year-old denim manufacturer based in South Carolina, as the looms’ best hope. “What would really be great to see is if Mount Vernon Mills could acquire those shuttle looms, and we could help to keep them running,” he told GQ in March.

Established in 1845, Mount Vernon Mills is a rare example of an American textile manufacturer that’s managed to not only survive the ravages of globalization and venture capital, but thrive. With six textile manufacturing plants across the Southern United States and 750 employees, Mount Vernon Mills produces more than a million yards of fabric each week. It’s also the country’s leading denim producer, supplying the likes of Wrangler, Levi’s, and Carhartt.

“I actually told a couple of folks to stop talking about [it],” says Bill Rogers, president of Mount Vernon Mills. “Because somebody from Japan, or somebody like that, was going to swoop in and try to grab the looms. So I said, ‘We’re gonna have to lie low and let the legal process play out, but I think I can get them.’”

When Vidalia’s assets were auctioned off in August—much to the surprise of those watching from the sidelines—the looms were not included in the sale. It turned out that the shuttle looms from White Oak weren’t actually owned by Vidalia Mills at all, but by an NYC-based company called KaKa Cotton. Their fate remained a mystery until last week, when Mount Vernon Mills announced that it had reached an agreement with KaKa to move the looms to its flagship plant in Trion and establish the first industrial-scale selvedge production line since White Oak.

“These looms are a national treasure,” says Victor Lytvinenko, the co-founder of Raleigh Denim. “Once White Oak closed, Vidalia gave it a shot, and it didn’t really work, but Mount Vernon has everything that’s needed to do it the right way. It's the only place in America that really could do it.”

Given the recent history of the looms that will soon arrive at the Mount Vernon plant in Trion, not to mention the ongoing challenges facing the American textile industry, anyone might be skeptical about the financial sense of weaving denim on antique machines in 2025. Despite this, Rogers is bullish that he can succeed where others have not. “Mount Vernon’s been in business 180 years and still going strong,” he says. “We’ve [also] got a viable denim business in other markets, so we’re not going to live and die by selvedge.”

To keep the machines running smoothly, Rogers’ team has begun combing old mills, factories, barns, and warehouses to source derelict machines and spare parts. He’s also hoping to partner with heritage groups like the Draper Museum in Lowell, Massachusetts, and the White Oak Legacy Foundation (W.O.L.F.) for training and expertise. If all goes to plan, he hopes to have a single-shift production line running by the spring.

“I can’t wait to see it,” says Lytvinenko, who is working through the final yards of his White Oak stash. As excited as he is to turn the Mount Vernon Mills-made selvedge into jeans, he doesn’t expect it to replicate the unique look of the stuff woven at Cone White Oak. “At Vidalia, the looms were on concrete floors, and they didn’t shake in the same way. It’s a really beautiful thing that can't be reproduced.”