For anyone who’s serious about selvedge denim, the name White Oak carries a lot of weight. Founded in 1905 by Cone Mills—the primary denim supplier to Levi’s, Wrangler, Lee, and countless other heritage brands for much of the 20th century—the Greensboro, NC plant and its legion of fabled Draper X-3 shuttle looms played a significant role in shaping the look and feel of traditional selvedge jeans.

When photographer Matt Sharkey got wind that the mill was shutting down at the end of 2017, effectively ending industrial-scale selvedge denim production in America, he grabbed a medium-format camera and headed for Greensboro. The photos he took on that visit and two subsequent ones would become American Denim: The Supposed Final Days and Resurgence of a Manufacturing Icon, a new book that documents the final days of White Oak.

The front office of Cone Mill’s now-shuttered White Oak plant.

Courtesy of Matt Sharkey

While American Denim focuses mostly on the plant’s transition from bustling factory to derelict industrial site, the book’s final section is dedicated to the handful of passionate preservationists at the White Oak Legacy Foundation and Proximity Manufacturing Company who are keeping the tradition of American selvedge denim alive. We spoke to Sharkey about his new book, his experiences in Greensboro, and why White Oak’s legacy matters.

GQ: How did you first become aware of White Oak?

Matt Sharkey: I started my own marketing consultancy in 2000, and Levi's was a major client at that time, so that was my first real education about White Oak. Then, in 2016, I was consulting for Chrome Industries, and they were working on a collection of denim with White Oak, so I went out to Greensboro to film there. That was my first interaction with the factory. But even prior to being at the factory, I'd known Tony and Pete, the owners of Tellason, for 15-plus years, and their denim was entirely woven at White Oak.

White Oak slasher Willie Capers Jr. tending to a beaming frame.

Courtesy of Matt Sharkey

You mention in the book’s preface that you were one of dozens who had submitted proposals to shoot at White Oak in its final days. Why do you think they chose you?

I've asked myself that several times. My hunch is that I was very honest about what's interesting to me about White Oak. In my eyes, this is one of the most important stories in American textiles and the idea that there wasn't any proactive thinking about how special it was and that it needed to be captured kind of blew me away. So I made a strong emotional plea, and I offered to fly myself out there and put myself up. Also, they had met me before when I had come out to film, and with my background in building brands and telling stories through images, I think it probably gave them some confidence that I understood what White Oak meant to the world.

Plastic sheets covering Draper X-3 shuttle looms in the weaving department.

Courtesy of Matt Sharkey

What do you remember from that first visit?

That first trip was completely eye-opening. I had never been inside a textile plant before, so the sheer volume when all the machines were running at the same time was really loud. The other thing was just seeing the pride on people's faces who were working there; you could see this pride of ownership in just about everyone. I was really moved by all of it.

Selvedge yarn being added to freshly dyed indigo yarn in the slashing department.

Courtesy of Matt Sharkey

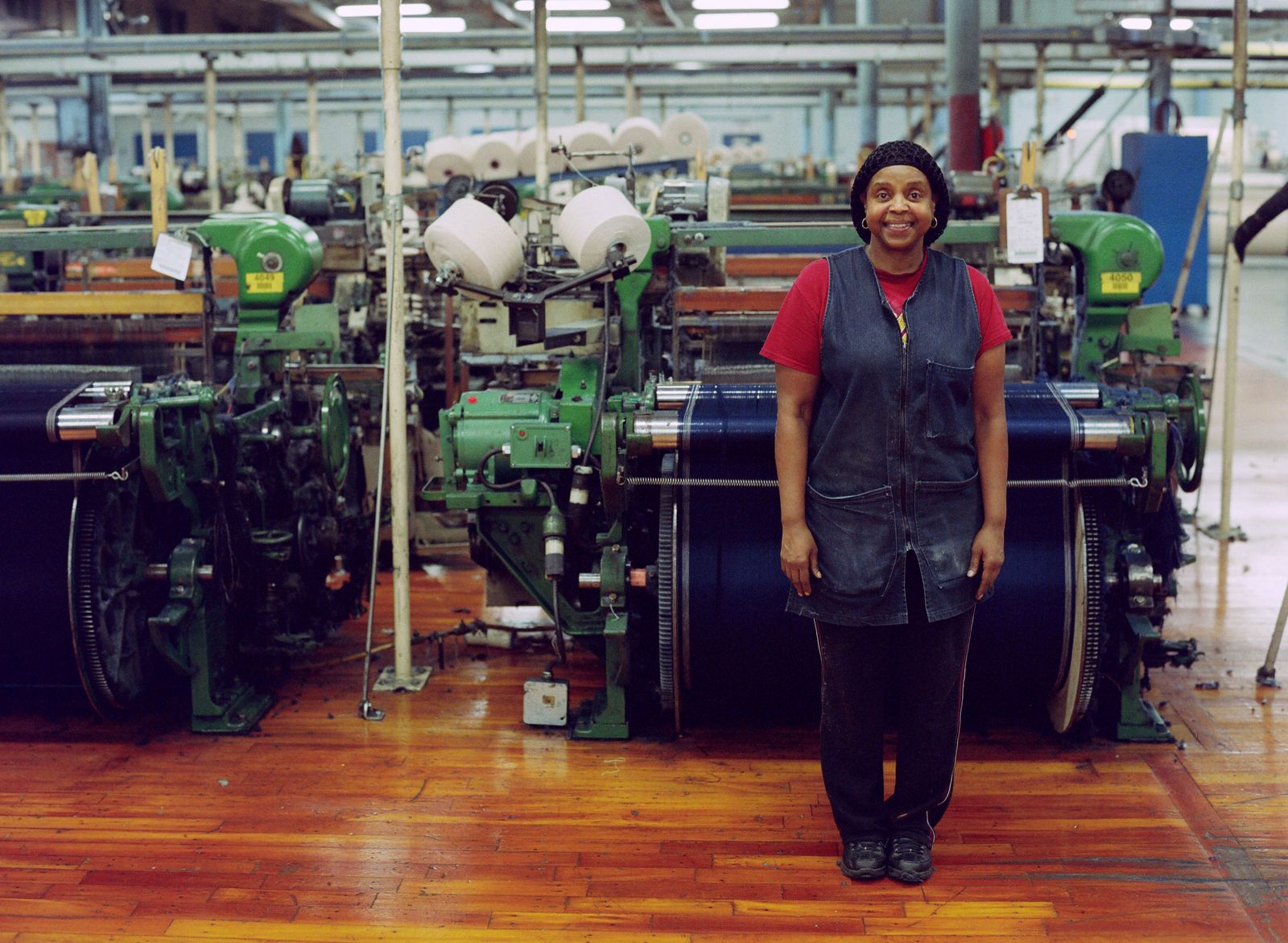

Based on your experiences and conversations you had with people you photographed, what kind of a place do you think White Oak was to work at?

It's hard to imagine Greensboro without White Oak. The entire neighborhood surrounding White Oak was built by the Cone family so that workers had a place to live, and you can feel a sense of what it was like in the 1940s. That level of pride was still incredibly evident in everybody that I spoke with, even though for some of them it was their last week. They were happy to talk to me about how long they'd been at a certain station, or what areas of the factory they had worked in over their career. And it was not uncommon for people to share with me that they were the second generation or even the third generation of their family to work there. I didn't get the sense from anybody that they were just working a job for a paycheck; it felt very much like they were very proud to be contributing to the legacy of White Oak.

Weaver Deborah Graves in front of White Oak’s sea of Draper X-3 shuttle looms.

Courtesy of Matt Sharkey

What was so special about White Oak’s denim?

I think what was special about it was just the legacy and how many years they were in operation. Its quality was also incredibly consistent, and that's why Levi's used them for as many years as they did, and it's certainly why Tellason used them. Nobody in the United States of America for the last 40 years had as many Draper X-3 looms as White Oak did. So if you were making a volume product like Levi's was, and like Tellason did, and wanted to do it strictly with selvedge, nobody else could have done that. I wear it every day, and I feel an incredible honor and pride to see that White Oak label.

Elbert “Frank” Williams, who worked at White Oak for 62 years.

In the preface to the book, you attribute White Oak’s closure to “a combination of corporate greed, government malfeasance, and the American consumer’s obsession with fast fashion.” Say more about that.

[The closure] probably felt abrupt to a lot of people, but I think it was a very slow death march. Globalization and significantly cheaper labor in other parts of the world had an impact, consumerism accelerated, and people started to expect lower prices and more different washes, different fades, and different treatments. Levi's was the largest buyer of White Oak’s fabric for well over 70 years, and they went from being a workwear brand to being a fashion brand. Fast fashion doesn't exist if people don't buy something new every season, and now there’s an expectation that a pair of jeans is never going to cost more than $65. I don't think one of those things in isolation is responsible for White Oak’s closure; it really was a perfect storm of circumstances.

Enormous tanks of indigo dye.

Courtesy of Matt Sharkey

The last section of the book is dedicated to the White Oak Legacy Foundation and Proximity Manufacturing Company, which is now weaving selvedge on a few of White Oak’s old X-3 looms in the plant’s old front office. What does that represent to you?

That chapter represents the spirit of the people of Greensboro and the desire not to lose what is now four generations of textile manufacturing. The White Oak Legacy Foundation and Evan Morrison [the director of Proximity Manufacturing Company] are not willing to let that skill and that trade be forgotten.

Vacated employee lockers in White Oak’s slashing department.

Courtesy of Matt Sharkey